In 1990, Health Affairs* reported “The escalating costs of prescription drugs and competition among pharmaceutical firms for customers are drawing the attention of policymakers, pharmacies, and individual and institutional purchasers. Mail-order pharmacies recently have grown in prominence as a competitive alternative to the local community pharmacy.”

With the improvements in retail pharmacy pricing, that motivation has diminished.

Some 26 years later, mail order is marketed as an approach to lower drug spend, but is also promoted to improve compliance of medication utilization. The theory is that a person is more likely to take the medications if they are delivered to their home. For employers, the question is whether the value to use mail order is greater than the potential waste for medications that are delivered, but never taken.

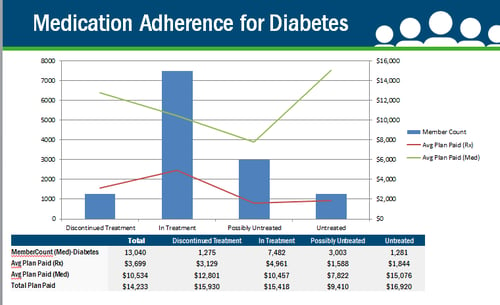

Since most mail order is delivered with no follow up to verify the person is taking the medications, there is little proof that delivering a medication actually improves compliance with taking the medication. The assumption made by proponents of mail-order pharmacy is that if medications are delivered to the home, a person will take them as required. In our database, we find the following gaps in medication adherence to refills.

Condition-Specific Prescription Gaps

| % of Treated Individuals with Two or More Prescription Gaps |

|

| Asthma | 31% |

| Hypertension | 10% |

| Diabetes | 22% |

| Lipid Disorders | 5% |

The most stated reason that persons stop taking medications is either due to cost, feeling better, or having problems with side effects to the medication. It is rarely that they didn’t have time to fill the prescription.

By having data that illustrates when someone fills their prescription, the provider or care coordinator has visibility into whether the patient is actively trying to comply with the prescription. That information allows one to understand if a prescription change is indicated or education related to the disease management is needed. That information is lost with mail order.

Why is this so important? In review of our data, in a pool of more than 13,000 individuals with diabetes, we find that 10% of the population stops filling their diabetic medications altogether. With some diabetic medications costing $1,300 per month, it is critical not to spend those resources unless someone is taking the medication.

Beyond persons being delivered medications that they have no intention of taking, there is also the potential of too many medications being delivered. We have seen a mail-order company delivering the 90-day supply of cardiovascular drugs at 60-day intervals and, therefore, overstocking the patients with medications. The pharmacy manager’s thoughts were that they did not want anyone to run out. However, that “overstocking” provided six months of extra medications in one year.

An employer also needs to consider if there is financial motivation for the PBM that is not passed on to the employer. PBMs have a financial motivation to promote greater use of medications since margin from mail-order pharmacies is their primary revenue source (for those PBMs that own their pharmacies). However, for employers, the savings from mail order can vary based on the discounts offered and the member cost-sharing in mail relative to retail. Accordingly, employers should be cautious about 90-day fills and auto-refill programs that mail-order pharmacies promote.

In conclusion, mail order may offer cost savings on specific medications, but when an employer decides to promote or offer mail order, they need to make sure the vendor provides any follow up to verify that medication is still needed. In specialty pharmacy, best practice is to call patients before shipping the medication to ensure they are still taking the medication. Ask your PBM/pharmacy if they offer this service.

Originally published by United Benefit Advisors – Read More